The growing shortage of paid caregivers has become increasingly apparent over the past several months. Now, we are seeing evidence of the most direct consequence of that scarcity: The cost of care, especially for those living at home, is rising faster than it has in years.

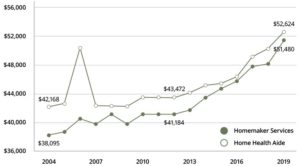

According to the newly released Genworth cost of care survey, the cost of homemaking services, such as cooking and cleaning, increased by 7.14 percent over the past year. The cost of home health aides, who provide personal assistance with activities such as bathing, dressing and eating, grew by 4.55 percent. The cost of adult day programs, a valuable service for both those living at home and their families, rose by more than 4 percent. For comparison, overall price inflation in the US grew by just 1.7 percent over the past 12 months.

As a result of these steep increases, which have persisted over the past several years, home care is becoming less affordable for many families. Genworth estimates that the annual cost of a full-time (44 hours-per-week) home health aide now averages $52,624, exceeding the average cost of an assisted living facility.

$23 an hour

Of course, many families use aides for much less time than that, but Genworth found that the average hourly rate of a home health aide hired through a non-Medicare agency is now $23, or $92 for a typical four-hour shift. Rates vary widely across the country, from $17.00 in Louisiana to $30.50 in Minnesota.

Also, keep in mind that these costs are for workers families hire though home care agencies and pay for out-of-pocket. Many families hire workers through the “gray market” who often are less expensive. And Medicaid pays agencies less than private pay rates (a reason why many home care agencies don’t take Medicaid).

Why are home care costs rising? In part it is because eighteen states increased their minimum wage this year.

But largely, it is due to a growing labor shortage: A growing economy means direct care workers can find easier work at higher pay in other industries. Others continue to work as aides but find jobs in hospitals or other institutions where pay and benefits are better. It isn’t an accident that home care costs have been rising since the US economy bottomed out a decade ago.

Of course, underlying all of these factors is growing demand for home care workers driven by an aging population, greater interest among seniors in staying at home, and the shrinking availability of family caregivers.

Another reason is the demographics of paid caregivers themselves. The current pool of experienced home health aides is aging out of the workforce. This physically and emotionally demanding work is difficult for those in their 50s and older, and 20- and 30-somethings are less interested in doing it.

Finally, there is the Trump Administration’s increasingly aggressive immigration policy. The advocacy group PHI International estimates that in 2017 about one-third of home care workers were immigrants, and about 14 percent were non-citizens. As that labor force dries up, the only way home health agencies can find willing workers is to pay them more. And that, it appears, is exactly what is happening.

This rise in long-term care costs may also affect those who own, or are thinking of buying, long-term care insurance. Until the past few years, the costs of supports and services was increasing by only about 2 percent annually. This suggested that people who were buying 5 percent annual inflation protection were substantially over-insuring (and paying a hefty premium to do so). And, indeed, recently consumers have been trimming back on those extra annual benefits.

But if the current cost trend persists, consumers may have to purchase additional inflation coverage, which would add to the price of already costly policies.

Rising home care prices also will affect public costs. It will create market pressures that will force government to raise Medicaid and Medicare payments for home care services. And it ultimately would the cost (or reduce the benefits) of public long-term care insurance programs. For instance, the $36,500 public long-term care benefit recently adopted by Washington State will buy fewer hours of home health care.

It is impossible to know from the Genworth study how much of the cost increase is going directly to workers, how much represents regulatory or other costs, and how much is added profit to home care agencies. I asked a couple of agencies and they insisted it is not profit. But there really is no way to know.

One thing is certain, however. Increasingly, families are unable to keep up with the cost of long-term care at home.

[…] The problem isn’t new. Low pay, low status, and physically and emotionally demanding work has plagued the long-term care industry’s ability to hire for years. Highly restrictive Trump-era immigration policies further shrunk the supply of foreign-born workers, who account for about one-quarter of all direct care workers. […]

[…] The problem isn’t new. Low pay, low status, and physically and emotionally demanding work has plagued the long-term care industry’s ability to hire for years. Highly restrictive Trump-era immigration policies further shrunk the supply of foreign-born workers, who account for about one-quarter of all direct care workers. […]

[…] The problem isn’t new. Low pay, low status, and physically and emotionally demanding work has plagued the long-term care industry’s ability to hire for years. Highly restrictive Trump-era immigration policies further shrunk the supply of foreign-born workers, who account for about one-quarter of all direct care workers. […]

[…] The problem isn’t new. Low pay, low status, and physically and emotionally demanding work has plagued the long-term care industry’s ability to hire for years. Highly restrictive Trump-era immigration policies further shrunk the supply of foreign-born workers, who account for about one-quarter of all direct care workers. […]

[…] The problem isn’t new. Low pay, low status, and physically and emotionally demanding work has plagued the long-term care industry’s ability to hire for years. Highly restrictive Trump-era immigration policies further shrunk the supply of foreign-born workers, who account for about one-quarter of all direct care workers. […]

[…] The problem isn’t new. Low pay, low status, and physically and emotionally demanding work has plagued the long-term care industry’s ability to hire for years. Highly restrictive Trump-era immigration policies further shrunk the supply of foreign-born workers, who account for about one-quarter of all direct care workers. […]

[…] The problem isn’t new. Low pay, low status, and physically and emotionally demanding work has plagued the long-term care industry’s ability to hire for years. Highly restrictive Trump-era immigration policies further shrunk the supply of foreign-born workers, who account for about one-quarter of all direct care workers. […]

[…] The problem isn’t new. Low pay, low status, and physically and emotionally demanding work has plagued the long-term care industry’s ability to hire for years. Highly restrictive Trump-era immigration policies further shrunk the supply of foreign-born workers, who account for about one-quarter of all direct care workers. […]

[…] The problem isn’t new. Low pay, low status, and physically and emotionally demanding work has plagued the long-term care industry’s ability to hire for years. Highly restrictive Trump-era immigration policies further shrunk the supply of foreign-born workers, who account for about one-quarter of all direct care workers. […]

[…] The problem isn’t new. Low pay, low status, and physically and emotionally demanding work has plagued the long-term care industry’s ability to hire for years. Highly restrictive Trump-era immigration policies further shrunk the supply of foreign-born workers, who account for about one-quarter of all direct care workers. […]